Uncontainable ascent

The playbook the US used to foil Japan's economic rise will not work against China

China is attempting to maintain development momentum by changing the internal drivers of growth from a massive investment expansion to more consumption-drawn growth, while increasing capital exports and pursuing various foreign direct investments. While some welcome such development because they need the capital and technology that China has at its disposal, others worry because their relative position in the global economy is weakening.

There is no straightforward analogy here, but some comparisons with the US-Japanese rivalry of the past come to mind. Although it was occupied by the United States for seven years after World War II, Japan was quickly able to put its economy on a path of rapid growth. While in the 1960s, the US' average annual rate of GDP growth was around 4.5 percent, it was as high as 10.4 percent in Japan (at this rate, income doubles in seven years). In the 1970s, the respective growth rates were around 3.2 percent and around 5.2 percent. In total, over the entire two decades, Japan's GDP grew by 347 percent, while the US' GDP grew by 113 percent. The acceleration of Japan's economic growth was the result of a policy of state interventionism, unique at the time, which some Southeast Asian countries later tried to emulate with varying degrees of success. However, the hegemonic position of US was challenged by the expansion of Japan, given the size of its economy and then still growing population. Although the two countries, lying on opposite sides of the Pacific Ocean, moved closer together within the same political camp, their economic relations were tense. It would be difficult to describe them as friendly.

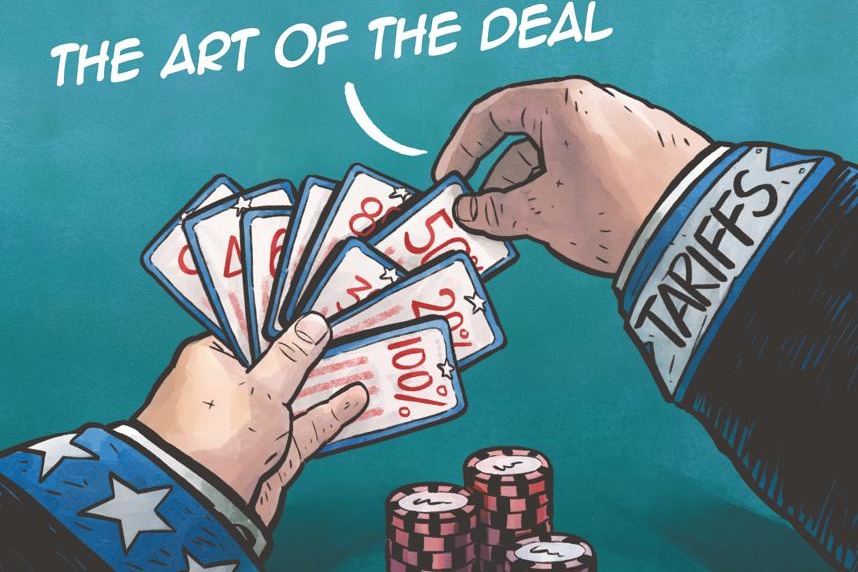

Peacetime had arrived and the Cold War was being fought on other dividing lines. Japan and the US became allies in the Cold War — and remained until today — but that did not stop Washington and Tokyo from waging a trade war. At that time, an adage was circulating in the corridors of power in Tokyo that trade is war. Japan wanted to win it, or, more accurately, this was a way to pay back for the humiliating defeat suffered by a generation or two earlier in the hot war. In Washington, they understandably wanted to win the war as well. A series of restrictions and protectionism were meant to slow down the growth rate of the Japanese economy, a supposed friend, but nevertheless a rival. For a long period, this did not work, but together with other factors, over time, it has had the desired effect for the US. In relation to Japan, it is often said that two decades were wasted. From the point of view of national income, this is how it can be described. According to World Bank data at constant 2015 prices, Japan's GDP in 2023 was $4.61 trillion, slightly larger than 20 years earlier, when it was $4.07 trillion. The US' GDP was $22.06 trillion in 2023 and $14.48 trillion in 2003.In other words, while the US' GDP grew by 52.3 percent over the two-decade period, it grew by only 13.3 percent in Japan.

Something similar is currently being plotted by the US with regard to China, but this time, it is a dream that is impossible to come true. And that is for many reasons, starting with the fact that China has a population over 11 times larger than Japan's and more than four times that of the US. Yet even more important is the diversity of economic dynamics. The differences in growth rates of China and the US in the next two decades will be smaller than in the previous 20 years, but unless some extraordinary circumstances occur, the average growth rate of the Chinese economy will still be higher than that of the US economy. One of the main reasons for that trend is the relatively larger share of industrial production in China's GDP, which has consistently declined but is still more than double that of the US — the respective ratios are about 38.3 and about 17.6 percent.

There is a big game being played to rationalize globalization. Alongside security and environmental concerns, this is the question of "to be or not to be" for our civilization. China can significantly help co-shape the desired future, limiting global dangers and the risk of a major catastrophe far beyond the economic field. The world is likely to face such a catastrophe if the economy is directed back onto the neoliberal business-as-usual track, and if the escalation of a new nationalism, including — or perhaps especially — that of "America First" and "Make America Great Again" is not contained. We can only hope that neither the neoliberal nor new nationalism biases will triumph, and this is largely — as increasingly recognized — owing to China.

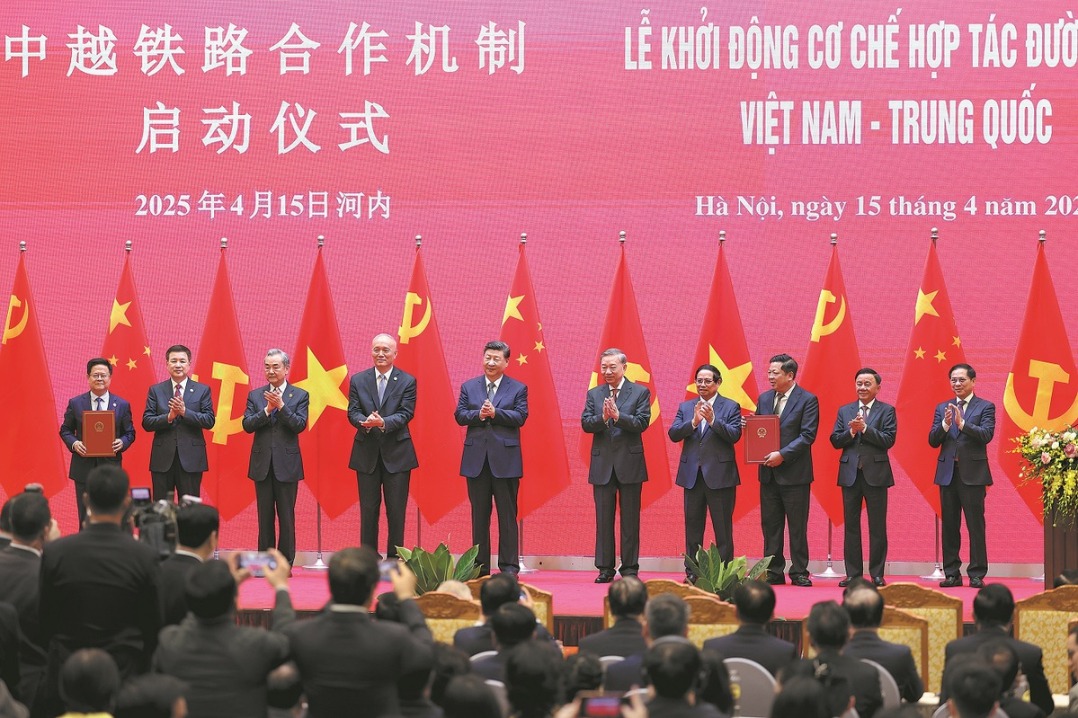

Of all the countries involved in globalization over the past three decades, China has been able to benefit the most through its wise and consistent policies. Importantly, it has done so not at the expense of others, but rather in positive synergy with foreign partners. This is one of the main differences between the approach to the globalization in China and the US, which is now clearly visible during Donald Trump's second presidency. I wrote more about this in my forthcoming book Trump 2.0: Global Disruptions and Power Shifts. Globalization is a long-term process of liberalization and integration of previously somewhat isolated national economies into an interdependent global market for goods, capital and technology. Particularly in technology transfer, China has benefited from globalization, first by absorbing a lot of it from more developed countries, but also in recent years by transferring a lot of capital and technology to others, helping poorer economies to accelerate their development.

Who is bothered by this? Why is it that, instead of praising China for its contribution to the development not only of its own economy, but also for stimulating the development of the world economy and helping other countries, we hear critical, even condemnatory opinions about Chinese development? Such criticisms often arise from misunderstandings or misplaced concerns, and they can sometimes provoke unnecessary jealousy, especially on the other side of the oceans — the Atlantic, looking from Europe, and the Pacific, looking from Asia. Some voices argue that China has hegemonic tendencies and its economic expansion as well as political and diplomatic activities are supposed to serve them, however, these views overlook China's consistent commitment to promoting mutual respect and win-win cooperation in international relations, emphasizing on open and inclusive development.

Some voices claim that it is the US' "values, however imperfectly they are realized, that still attract people from all across the planet, in a way that Chinese communism does not". During Trump' second presidency, they will attract less and less. As a result of the pro-development nature of the Belt and Road Initiative, and particularly the positive example set by the achievements of the Chinese way out of poverty, US values are losing their attractiveness in the eyes of the less economically advanced countries, while China's values are becoming increasingly appealing.

The author is director of TIGER — Transformation, Integration and Globalization Economic Research — at Kozminski University in Warsaw, former deputy prime minister and minister of finance of Poland, and a distinguished professor at the Belt and Road School at Beijing Normal University. The author contributed this article to China Watch, a think tank powered by China Daily.

The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

Contact the editor at editor@chinawatch.cn.